|

One of my very favourite tools for taking stock is a values assessment. Values define who we are and what matters to us. When we find ourselves in situations where our values are compromised, we can become stressed and anxious. When we hold goals that are in conflict with our values or don’t address enough of our values, we tend to procrastinate because the tension stops us being able to make progress. Values do change over time depending on circumstances. By being aware of our values, we are in a better position to:

Use this list to identify the 10 values that are most important to you. Then order them in terms of their importance to you.

Click here if you would like an at-a-glance page summarising the tool. Please get in touch if you have any questions and do share your experiences of using this tool in the comments area below.

0 Comments

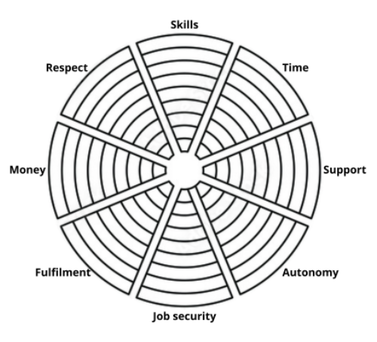

My favourite starting point for taking stock is to take a measure of where you are right now, in a holistic sense, to answer the question “how are you doing in all areas of your life?”. The Wheel of Life is a great tool for that. In its most basic form, it is a circle divided into 8 sections. Each section is devoted to an area of your life. The example on the right focusses on career, but the tool can be adapted to suit whatever circumstances you need to explore. Essentially, you rate each area of your life on a scale of 1-10 in terms of how satisfied you are with that facet of your life and then how important it is to you. The second rating is very important because it isn't worth spending time on on something that you don't care about much! You might find it useful to use a table like the one below: By getting it out of your head and on to paper, you are able to see how you are doing and how important that is to you. It helps you decide what needs your attention and offers a glimpse of what might happen if you chose not to pay attention.

Click here if you would like an at-a-glance page summarising the tool. Please get in touch if you have any questions and do share your experiences of using this tool in the comments area below. TL;DR - make sure that your behaviour doesn’t inadvertently trigger a threat response in other people! Neuroscience tells us that our desire to minimise threat and maximise reward is what motivates our behaviour. And the part of our brain that governs this is our most primitive brain, the amygdala, which also looks after our basic survival needs. This totally makes sense from a species development perspective - we need to be able to quickly discern what is dangerous and what will help us thrive. It turns out, according to the SCARF model (Rock, 2008), that co-locating these two functions in the limbic system means that we respond to social threats and rewards in a similar way to physical threats and rewards. We are very quick to decide if something is ‘good’ or ‘bad’ for us and take action accordingly. In fact, that part of the brain can react faster than we can actually think, so its more of a reflex than a conscious thought. The SCARF model looks at our lighting fast responses to 5 areas of human social experience: Status, Certainty, Autonomy, Relatedness and Fairness and how humans process information in those areas in order to decide if someone else is a friend or a foe. The model was originally interpreted in an organisational context, to help leaders engage with their teams better but it has potential for much wider application.

Status There is research that suggests higher status individuals (also seen in ape communities) live longer than others, due to having lower baseline cortisol levels. Many animal social units are structured around just one adult male in the group, to ensure genetic survival and any threat to that is fiercely defended. Being higher status also helps to guarantee increased access to basics like food, water and shelter - and often much more than that as well. With survival at stake, we do not respond well to threats to our place in the social pecking order. It activates the parts of the brain involved in the perception of physical pain. Sometimes the 'threat' is unintentional: giving advice and offering criticism are the types of experiences that are interpreted as a status challenge and thus seen as being highly dangerous. On the other hand, praise, recognition, promotion, responsibility and access to information are seen as rewards and with this insight its easy to see how the way that we treat people will be interpreted by them at an instinctive level and cause cause them to respond in a way that that can have a huge impact on our own survival. Certainty In order to not over tax or brain resources, we tend to rely on pattern matching to identify situations where we need to focus more intently. Which is why its possible conduct familiar tasks on auto-pilot and almost be mentally elsewhere, for example, while driving a car on a routine journey. Unexpected events, like a dog crossing the road, jolts us back into consciousness. When humans are in situations where they can’t relax into a comfortable predictable pattern, they experience ongoing low level stress, which impairs the function of the orbital frontal cortex. The impact of this is not insignificant because it can significantly reduce productivity. Conversely, certainty triggers dopamine, the reward hormone. We can create a sense of certainty by, where possible, being clear about what is going to happen, establishing and sticking to routines and keeping people up to date. Autonomy Research indicates that loss of autonomy - the ability to have some control over one’s environment - can impact our cognitive ability, mental health and ultimately our physical health. Being micromanaged can trigger a threat response and being in a team basically invites less autonomy due to the need to cooperate and work together. Giving people choice and a sense of control can minimise the threat response and even increase a sense of getting a reward. Relatedness Being part of a group was, for our ancestors, a matter of life or death and exclusion was a terrifying punishment. Humans are very skilled at assessing whether someone is safe to trust or not. Relatedness is our sense of safety with others and being part of a group. Lack of relatedness, when a person feels excluded, can reduce creativity, commitment and collaboration - essentially, they withdraw. When a person feels connected with others, Oxitocyn is released and creativity, commitment and collaboration increase. We can make people feel more included in a range of ways, from shaking hands to exchanging a bit of small talk and, in a work context, including them in conversations and making decisions. Fairness A number of studies have shown that fairness is an important motivator for us and is intrinsically rewarding to humans. A perceived increase in fairness and a financial reward both activate the same part of the brain. A sense of unfairness lights up the same part of the brain that responds to disgust and can be the motivator for political struggles and more. Unfairness at work can affect mental and physical health. To avoid triggering a threat response based on unfairness, be clear about rules, the logic that drives decisions like task allocation and reward structures.

The SCARF model can be applied in many areas of life, from self-management, to educational and leadership development. Once we understand why we and others feel threatened, we are able to use alternative strategies that focus on the reward response to get the outcomes we are looking for.

References

The dictionary definition of resilience is: the capacity to recover quickly from difficulties; the ability of a substance or object to spring back into shape; elasticity. It's a subject of great interest at the moment because many of us are having our ability to "bounce back" tested by the coronavirus.

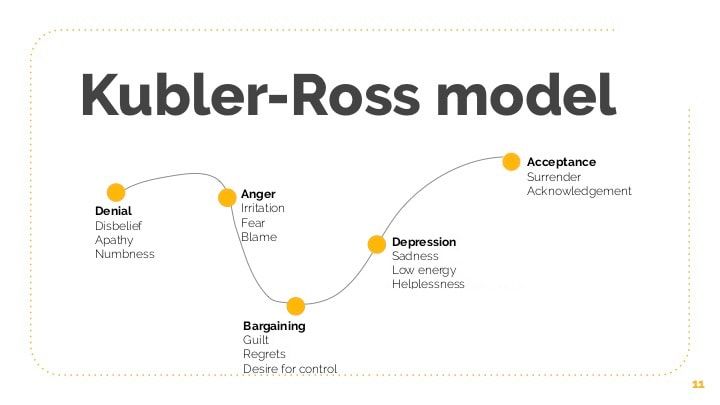

A model that comes up a lot is Elisabeth Kubler-Ross' five stages of grief theory, which was published in the late 1960's. Her experience with terminally ill patients led her to observe a pattern of thinking that people go through when facing death either themselves or in a loved one. This theory was later found to apply to all kinds of personal loss including disability, redundancy, divorce and financial problems. It's not a linear process: people can go through it at any pace, in any order and often experience cycles of it. These are the phases:

Image courtesy of Narayana Health I grew up in a household where logic and rationality were valued and rewarded. Emotions, along with acting in ones own self-interest were seen as disdainful, weak and embarrassing. As a result, I have not only spent decades priding myself on keeping my needs and feelings in check, I believed that getting emotional at work - crying - was up there with the top 3 career killing moves of all time. Something to be avoided at all costs, along with yelling at your boss or turning up drunk (although the severity of this may depend on the company culture and the country you work in!)

Over the years, while I revelled in my skill at remaining rational and unemotional at all costs, especially at work, I began to have nagging doubts about whether the life plan I was following was actually the right one for me. I began to wonder if I was really pursuing my own dreams and whether my goals were truly mine or not. I would torture myself with the question of what would I do if I won the lottery and didn’t need to work for a living. None of the answers I gave myself, other than developing cirrhosis of the liver, seemed genuine and believable. It certainly made me feel a bit pointless. From time to time, I found myself in a situation that encouraged reflection and consideration of purpose, my instinctive response is that I wanted to get better at “following my heart” - which felt at the time like it was locked away in a inaccessible vault - so that I could understand my purpose in life and be the real me. I tried for many years to spring the lock and get access to my true feelings. Like the story of the Golden Buddha in Wat Traimit, that was hidden in plain sight by ugly concrete and protected from Burmese invaders, it turns out that my feelings had been plastered over by a ton of beliefs I picked up as a child, that may never have been true and were definitely not useful to me as an adult. A few things have helped me strip back the layers and tune into my heart. I thought I would share them here:

As someone who is setting up a new business, I know I need to make a lot of noise about it so that people know I am here and what I have to offer. I was doing pretty well on that front, especially for an introvert, but that stopped as soon as we went into lockdown.

Looking back at my silence, I realise it was prompted by a number of factors

I work with a lot of people who struggle with stakeholder management. They spend a lot of energy beating their head against a brick wall trying to get their boss/budget holder/leader to think differently. As almost all of my clients are digital, agile, user-centred people, they have the key to unlock this particular problem firmly in their pockets but they seem to have forgotten that it’s there. It’s going to be even more important now that we are all working remotely as its harder to build relationships at a distance.

When it comes to product management, people are very accustomed to exploring users’ needs, interviewing and observing users and collating insights so that they and the team can easily step into the user's shoes at will. It’s been a while since I’ve seen a product in development that does not test with users incredibly frequently, to make sure all new features are useful and usable. My suggestion to you is to take this same user-centred approach to stakeholder management. You need to treat them like you would any other user of the system you are working on and observe your boss/budget holder/leader until you know exactly what makes them tick. You might even want to make a persona for them, just as you would any other user! Making life easier for them must be a priority for you! Your research needs to uncover:

Once you understand your boss/budget holder/leader, take a look at the subject you are championing or campaigning for and see it through their eyes. From that perspective, consider how important is going to be to them. If you were your boss/budget holder/leader, would you still be pushing for the same things as you do now? I’d love to hear thoughts on this, especially from people who have tried it! Otherwise, what's your secret to handling tricky stakeholders? Life is full of surprises; some are good and some are not so good. Our ability to stay flexible and positive under pressure can have a huge impact on our wellbeing. Resilience is not an innate capability; it's more like a muscle that can be built and strengthened. There are 4 pillars to well being: mental, physical, emotional and social. Each of these can be fortified to help us handle life's ups and downs, reducing the negative impact and allowing you to take it in your stride. In this session, we will talk about a few research-backed techniques that can help you bounce back when you need to.

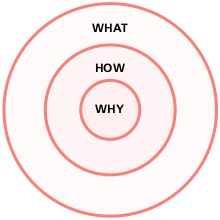

I loved Simon Sinek’s Start With Why. It felt like he had explained how the world should work. His basic premise is that that we can inspire others by putting the Why (the purpose) before the How (the process), or the What (the product) because it builds an emotional connection. Apple are a great example of a company that do this very well. They have customers who adore them and wait all night in the rain to be the first to use a new product. I have a strong “bullshit radar” and it is triggered by inauthentic people and organisations. At times it gets so loud, it interferes with my ability to think and function well. I have found myself at odds with people and employers because I find their lack of integral harmony deeply disturbing. Thats not to say I expect everything to be totally aligned all the time. I also have a huge amount of sympathy for people and businesses that are trying to navigate in imperfect circumstances and have to compartmentalise parts of themselves in order to appear to be sane. A degree of incongruence is a fact of life and we need to be very understanding about that. It’s just when the dirt they have been sweeping under the carpet gets to be bigger than they are, its definitely time to acknowledge it and see what needs to be done. Usually, people or businesses that trigger my authenticity radar simply do not have a true reason for being. They are normally caught up in the pursuit of a very narrow focusses success (money or fame) rather than being driven by a true mission or vision. This leads to them saying or doing whatever it takes to get them towards their goals. We’ve all met a few of them or seen them on reality TV programs. Some of the extremely “successful” ones have been able to take public office. Simon Senek’s book is terrific at explaining the benefits of finding your true purpose, but less good on the how. His second book, Find Your Why, aimed to help us all find our purpose, has turned out to be less helpful. You are reliant on having a very astute and insightful friend to point it out to you. Sadly, I and others lack such friends.  Another approach is using Héctor García and Francesc Miralles approach in Ikigai: The Japanese Secret to a Long and Happy Life”. The Japanese letters used to denote, ikigai represent “life” and “to be worthwhile.” Everyones’ Ikigai will be different and some seem more ambitious than others, but having a sense of meaning can contribute to a longer life and improved well being. The Japanese believe we all are born with an ikigai, we just have to find it. The process is simple, you need to find:

And the intersection of all of those things is your ikigai, your reason for being. Finding your purpose is very liberating. It becomes the compass that guides your life. Suddenly, it’s a lot easier to make decisions because you know what to focus on and what is ok to let go. I recommend you try it. You’ll need to spend time looking back over your past, at what you have enjoyed doing over the course of your life and see if you can recognise any patterns or themes. When I did it, I noticed a thread that runs through my life which is about making life easier for people. My original degree was in design. I wanted to mass produce things that would add joy and simplify peoples lives. When I “fell” into the digital world, I quickly found a home in user experience design, again driven by a desire to create experiences that was shaped by the customers wants and needs, not asking them to contort themselves to the shape of the business. And now, as a coach, my driving ambition is to help people find a way to navigate their lives towards what brings them joy and fulfilment rather than being pushed around by false beliefs that have accidentally acquired from childhood onwards. Finding your life purpose on your own isn’t always easy. I've made a cheat sheet to help you do it. If you need some help, give me a shout. Photo by Michael Kaufmann from FreeImages Life is full of surprises. Some are great (marriage, babies, new opportunities) and some are not great (separation, redundancy, ill health, loss of a loved one) but all of them require adjustment to a new reality, and often a new sense of ourselves. Even navigating through happy changes, a person starts off as single, then becomes part of a couple, become a spouse and/or a parent. All new identities, new ways of seeing ourselves and being seen. Some we just leap into fearlessly and some are accompanied by some degree of trepidation.

Less happy changes involve loss, which often need to be mourned. While the phases of grief are well known: denial, anger, bargaining, depression and acceptance (Kübler-Ross, 1969), having a recognised model for it can help normalise the turbulence experienced in the transformation process. In our society, certain losses, like death and illness tend to elicit more social acknowledgement and therefor support than others, like divorce and retirement. Martha Beck (2001) suggests there are three phases to making changes once a catalyst for change has hit your life: Birth and rebirth Especially if the change is significant, there can be a strong resistance to change and there is a temptation to treat it as “just a blip”. An example of this is seen in unhealthy relationships where poor behaviour gets hidden or excused rather than facing the upheaval required to make significant changes. A lot of the resistance is tied up with identity and the requirement to change the way we see ourselves. The person in an unhealthy relationship may have many negative associations with being single, not being able to maintain a relationship, etc Change is only possible when there is an acceptance that the old status quo is unsustainable and needs to be dissolved in order to be reformed into something new and improved. There may be a need for time to mourn the loss of the old sense of self. And to get comfortable with what might seem to be uncomfortable and ill fitting at first. Dreaming and scheming In order to move forward, we need a sense of what the future could look like. Having a compelling vision is a great motivator for many people and helps them summon the energy required to make a leap into the unfamiliar. Hero’s saga This phase can take the most time. As you start to take action, reality invariably intrudes and, depending on the scale of the change, the journey could be very choppy and challenging. At some points, adjustments (in either the vision or the implementation) will have to be made. Some options that seemed so promising may turn out to be less fruitful and unexpected opportunities will present themselves. Tenacity and flexibility are key in this phase, as well as the need to keep the origin vision in mind, in order to not lose hope and confidence. Success! The transition is completed Time to celebrate and really soak up the sense of achievement! But be careful about assuming you can rest on your laurels. One certainty in life is that everything changes so make sure you are keeping an eye out for new catalysts (good and bad) that will herald a new transition. But the great news is now you understand how it works and what to expect, which will help you get through it again. Do bear in mind, there are all sorts of experts who can help you through these difficult times and asking for support could well help make the journey less of an upheaval. In terms of getting support through a transition, I can only speak from a coaching perspective. A coach can:

If you feel like you are struggling with some kind of transition, it's important to get some support where you need it. Culturally we are often reluctant to ask for help but, when you do, it's such a relief to be able to talk it through with some one else. Even the process of hearing yourself talking about it allows you to think about it differently. And most people find that a problem shared is a problem halved. And if it isn't, there are many professionally trained people, myself included, who would be able to help. References Beck, M, Finding Your Own North Star, 2001 Kübler-Ross, E, On Death and Dying, 1969 |

Author25 years experience in helping teams build user centred products and services, now helping digital colleagues learn how to bounce back better than before from the challenges life throws at us from time-to-time. Archives

December 2022

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed